Tech entrepreneur from Baltimore started the nation’s largest Black-owned fintech platform, a peer-to-peer microlender

- December 3, 2023

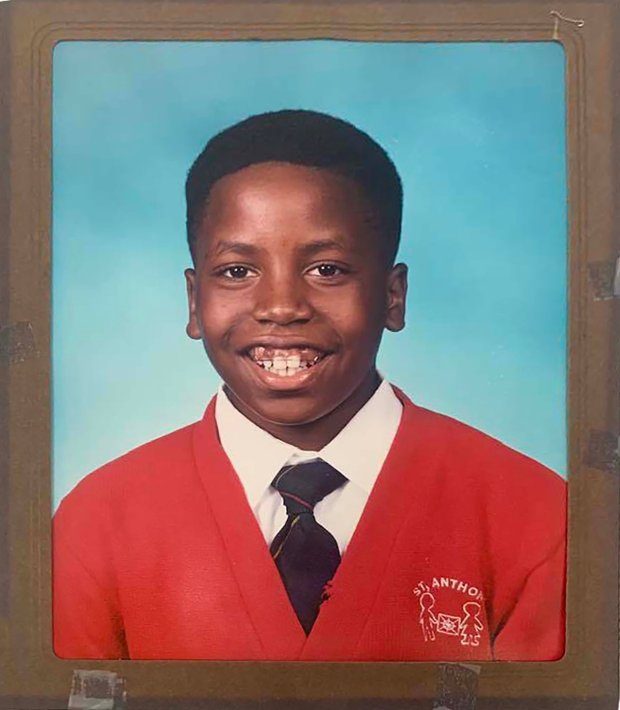

Rodney Williams fondly recalls his days growing up in Northeast Baltimore, when he ran track, acted in drama classes and played high school football.

The tech entrepreneur, now 39, also remembers how his mom and other family members struggled to make ends meet.

His experiences led him in 2018 to create an online, peer-to-peer lending marketplace that he describes as “democratizing finance.” Earlier this year, SoLo Funds Inc. hit 1 million registered users, becoming, it says, the largest Black-owned consumer fintech — financial technology — company in the U.S.

The growth leaves no doubt about a huge unmet demand for a community finance alternative to high-interest credit cards and payday loans for borrowing small amounts, Williams said, especially among those living paycheck-to-paycheck or facing borrowing barriers.

“I just saw how hard it was for my mom to get out of the trap,” said Williams, who started SoLo in New York City with his best friend Travis Holoway as co-founder and CEO. “There always tended to be a gap between when a bill was due and when she was getting paid. It wasn’t that it wasn’t coming. It was a matter of ‘Oh, my God. The electricity is going to be off on Wednesday,’ and she doesn’t get paid until Friday.”

Online peer-to-peer lending has existed since the early 2000s as an alternative to banks, but most sites offer larger loans than SoLo, where users can borrow no more than $100 the first time. If that’s repaid on time, the amount increases to $575 for subsequent loans. Since such peer-to-peer lending began, it has raised questions about how to protect both its borrowers from predatory terms and its lenders from losing their money.

On the SoLo marketplace, users can ask to borrow for up to 35 days on their own terms and lend to other members. Borrowers can choose to tip lending members or make a donation to SoLo but are charged no mandatory fees. They technically pay no interest but end up paying the equivalent of an average annual interest rate of 13.4% on loans via the tips and donations, according to SoLo.

SoLo says it has a 93% repayment rate and a 6.8% default rate.

Lenders can see scores showing the likelihood of repayment, based not on borrowers’ credit scores but on their cash flow as determined by their bank account activity. Just over half of requested loans get funded, most within 15 minutes, Williams said. If lenders decide to pay an optional protection fee, SoLo repays a portion of the loan if a borrower defaults.

The company, now based in Los Angeles where Williams lives, has piqued the interest of some of the biggest names in Black venture capital, including Shea Moisture founder Richelieu Dennis’ New Voices Fund and Kesha Cash’s Impact America Fund. But the business also has drawn scrutiny from regulators who have accused SoLo of deceiving consumers about the true cost of loans on its platform.

Williams said it’s a testament to a peer-to-peer, micro-lending model he calls transparent, empowering and misunderstood that it has not only stood up to the regulatory scrutiny but is poised for growth.

“Our model does not fit current regulatory models, yet there is enough good here in this model for regulators to allow us to operate moving forward,” Williams said.

SoLo, with about 90 mostly remote workers, says it has facilitated more than $200 million of personal loans. The platform is on pace for a 300% jump in volume and revenue this year compared with 2022. More than 80% of lending and borrowing members live in underserved Zip codes.

To date the company has raised about $30 million from investors, including a seven-figure investment about a year ago from a venture capital fund run by tennis great Serena Williams, whose Serena Ventures began actively investing in startups nine years ago.

“We are proud to stand behind SoLo as it continues growing at an incredible pace and focuses on giving underserved groups and individuals the tools they need to thrive financially,” the 23-time Grand Slam winner said in a news release when SoLo reached 1 million registered users in February. “Community finance is working, and SoLo is proof of that.”

Still regulators in California, Connecticut and Washington, D.C., did bring consumer protection cases against the company. SoLo settled those complaints in May, allowing it to resume operating in those places. It admitted no wrongdoing but paid some penalties and agreed to make additional disclosures about donations and tips being voluntary.

The complaint by the Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia alleged SoLo loan marketplace was deceiving consumers about the true cost of loans, saying that borrowers paying a “tip” to lenders ended up paying more than 500% annual percentage rate in interest on average, far in excess of the district’s 24% cap.

It also alleged that SoLo advertised no interest and no fees but required borrowers to tip lenders a percentage of the loan and make a donation similarly to the company. The marketplace also advertised that lenders could make a quick return on extra cash, but never disclosed that borrowers often either failed to repay on time or at all, the lawsuit said.

“Our office will not tolerate Fin-tech lenders resorting to new, deceptive practices that adversely impact vulnerable residents who are frequently ineligible for traditional loans,” Attorney General Brian Schwalb said in a news release. “SoLo sought to disguise exorbitant interest charges by deceptively calling them ‘tips’ and ‘donations.’”

Under the settlement, the company agreed to clearly disclose that tips are optional and that the borrower’s decision on whether to tip or the amount of the tip would not impact the ability to borrow. And it agreed to offer “honest disclosures” about how much a lender can expect to earn.

It also paid $30,000 in D.C. and $100,000 in Connecticut, mostly refunds to customers.

A spokesperson for the Maryland Attorney General’s Office said its consumer division has received no complaints about SoLo.

In resolving the complaints, SoLo officials said the scrutiny stemmed from misunderstandings about its mission and business model.

Williams defended the practice of “tipping,” as common to many service industries. The tips go to members on the site, not to SoLo, he said.

“When you drive innovation, that means there may not be specific laws that regulate what you do, but that doesn’t mean it’s not the right thing for the consumer,” especially those who’ve been overlooked and lack options for short-term capital, Williams said.

Other small loan apps that have similar models include Dave and MoneyLion, while others such as DailyPay, FlexWage and Payactiv work with employers to give employees access to wages before pay day.

Microlending can be a big help for people in difficult short-term situations who would otherwise have no access to credit other than payday loans, which are able to charge high interest rates in part because of the risks and costs of such loans, said John Dougherty, an assistant professor of economics at Loyola University Maryland’s Sellinger School of Business and Management.

“A peer-to-peer system makes a lot of sense,” as long as borrowers clearly understand the costs and lenders understand the risks, said Dougherty, who has done research on microfinance projects that helped farmers in Ghana and Tanzania.

Microlenders may be motivated by the ability to both make a return and help make a difference for someone in a situation that resonates with them, he said.

Williams traces the idea for the business to his mother’s struggles as he was growing up in the Garden Village and Frankford/Cedonia areas. His mom, Janice Williams, worked two jobs, as a beautician by day and nurse at Franklin Square Hospital by night, but “she would often get denied for credit cards and payday loans,” he said.

His mother and other women in the neighborhood supported one another financially through savings clubs, where friends would pool savings to be accessed during emergencies.

He also credits his mother for emphasizing education and activities as a key to his future. Williams attended Calvert Hall College High School, where the 2002 graduate played football. He also ran track as a teenager with the Baltimore Edward L. Waters Track and Field Alliance Club, a youth sports club that has several Olympic competitors among its alumni. During middle school, Williams attended an after-school drama program at the Baltimore School for the Arts and was involved with Arena Players.

“These were the programs that definitely kept me away from other things,” said Williams, the youngest of six brothers.

He earned degrees from West Virginia University in business, finance and economics in 2006 and then a masters in marketing. He went on to get an MBA from Howard University.

His first job as a brand manager for Procter & Gamble in Cincinnati led to the co-founding of his first company in 2012. Lisnr, a mobile payment technology firm, grew out of a Procter & Gamble-led business incubator. Lisnr, where Williams served as CEO and still is chairman, has raised more than $40 million to date, including through technology accelerators around the country.

He began looking into the financial services sector after noticing, during trips home to Baltimore for holidays, that family members and friends often found themselves in one tough spot or another, needing $50 for gas or $300 to keep the lights on, despite having jobs and sometimes college degrees.

“It was much bigger than my friends and family,” Williams said. “It was a middle-class American problem. All of our financial products are built for people who have money. They don’t build products for people who have limited money,” or jobs but no substantial savings.

Meanwhile, he said, people with limited savings are not seeing their savings grow.

He wondered how he could connect those two groups so they could help each other, he said, ”where one group can make a request and choose how much they’re going to pay, and another group can fund.”

Alvin C. Hathaway Sr., retired pastor of Union Baptist Church in West Baltimore, said SoLo is addressing a problem he sees in Baltimore neighborhoods, lack of access to small amounts of capital other than payday loans and check cashing outlets that can be exploitative.

Hathaway said he has known Williams since he was a child. Williams ran track and attended school with Hathaway’s son, and the two ran an event promotions business during college.

“When I think about Rodney, I think about him as a young man, very disciplined, who pursues his goals and objectives and does not get distracted,” Hathaway said. “He takes what you would think is adversity and turns it into opportunity.

“He’s an entrepreneur that looks at problems and tries to develop solutions, and he understands technology to be able to bring that to fruition,” Hathaway said.

Williams has become something of an ambassador for a growing technology hub in Baltimore, said Kory Bailey, CEO of UpSurge Baltimore, a tech “ecosystem building organization.”

Williams has participated with UpSurge in Baltimore Homecoming events in San Francisco and in Baltimore, where his mother, father and brothers still live. Bailey lists Williams among a handful of Black tech company founders from Baltimore who have huge name recognition and influence on the city’s tech scene.

“He’s really well known both as a tech founder and sort of a cultural icon,” Bailey said. “A lot of times when we think about folks that our young people look up to, we think of our athletes and entertainers, but Rodney has really positioned himself as an entrepreneur… that young people can look up to and say, ‘I want to be that person one day, and I want to follow in the footsteps of that person who came from where I come from.’”

As for SoLo, Bailey said, Williams is using technology to help marginalized communities get access to short-term loans in a way that isn’t predatory.

“I think it’s disruptive,” Bailey said. “It really is putting the payday lender space on notice to say hey there are different models out there that can be created to get people what they need.”

Sign Up For Our

Newsletter

Each day, we honor and remember those who have recently passed away.

Most Viewed

More

- Article Obituaries

- Celebrities

- Celebrity News

- Local

- News

- News & Advice

- NFL

- NHL

- Northside

- Norwin

- Obituaries

- Obituary

- Penn Hills

- Pirates

- Pitt

- Pittsburgh

- Plum

- Politics Election

- Sports

- Steelers

- Theater Arts

- Top Stories

- Travel

- Tribune Review Obituaries

- US-World

- Valley News Dispatch

- West End

- Westmoreland

- World