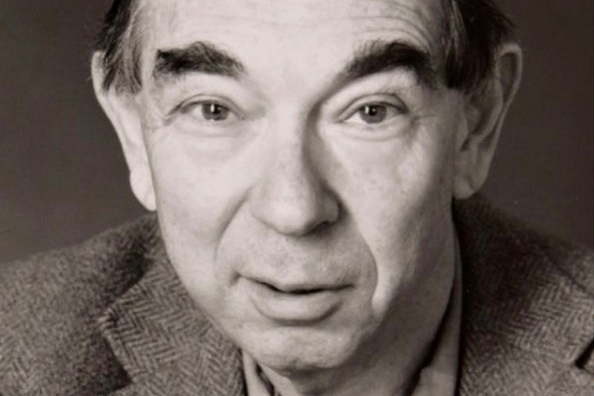

Louis Kampf, professor emeritus of literature and women's and gender studies, dies at 91

- August 14, 2020

Louis Kampf, professor emeritus of literature and women’s and gender studies at MIT, died in hospice care on May 30 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at the age of 91. The cause was cardiac arrest.

The only child of Oscar and Helen Kampf, he was born on May 12, 1929 in Vienna, where his orthodox Jewish parents had migrated from Galicia, Poland. Between 1938 and 1942, he and his parents fled the Nazis, first going to Antwerp, Belgium, and thereafter to France, where Kampf’s father was interned as an enemy alien. Kampf and his mother traveled, with great difficulty, to Bagnères-de-Luchon in the Pyrenees in Vichy France and then to Marseilles and finally Casablanca, from where, in 1942, the family caught a “Companhia Colonial de Navegação” ship to the United States.

By 1943, Kampf was fluent in German, French, English, and Yiddish and was learning Hebrew at a Yeshiva. He had read widely in literary classics, and was building the encyclopedic knowledge that distinguished his conversation throughout life. He graduated from George Washington High School, pursued an English major at Long Island University — where he was the sixth or seventh man on LIU’s national championship basketball team — and went to the University of Iowa to pursue graduate studies in comparative literature. In 1958, he went to Harvard University as a junior fellow in the Society of Fellows at Harvard; it was a three-year fellowship, and he spent his last year at the American Academy in Rome. In 1961, he gave the Lowell Lectures at Harvard, revised and published as “On Modernism; The Prospects for Literature and Freedom” (1967), which won a Modern Language Association prize.

To MIT and the MLA, in a time of turmoil

He joined the Literature section of MIT’s Humanities Department in 1961, and chaired the Literature faculty from 1967 to 1969. In 1968, at a tumultuous meeting of the Modern Languages Association, Kampf was nominated from the floor and elected as second vice-president by popular acclaim, which meant he would succeed in two years to the organization’s presidency. The MLA’s leadership was appalled: They had already announced the election of their chosen candidate, as had been done for many years. But America was in turmoil and Kampf, already known as an activist, represented the kind of change many of those gathered at the meeting in New York were demanding of their professional association, as well as of their country.

The next year was one of political turmoil, with protests both peaceful and roiling campuses. In December of that year, Kampf was elected president of the MLA. He had no wish to hold that office, but obligingly fulfilled its obligations as a slightly bemused but dutiful president and as founder and shaper of its Radical Caucus.

A new lens on literature and imperialism

Although Kampf had always had an omnivorous appetite for everything connected with Western high culture — music, painting, literature and philosophy — his attitude shifted in the course of the Vietnam War. MIT Professor Emeritus Alvin Kibel remembers it thus: “Louis had been a sly, self-amused, captivating person, expounding Joyce and Proust and Diderot in a markedly graveled New York-Jewish accent. Now, as the U.S. had become more deeply committed to its Vietnam misadventure, Louis had come to regard the established high culture as, among other things, the product and agency of imperialism; and he thought it more important to resist this imperialism than to expound texts that, for all their value, were ideologically complicit in it.”

Together with Richard Flacks and John McDermott, Kampf was a key participant in the late 1967-early 1968 founding of the New University Conference (NUC). Born in the wake of the dissolution of Students for a Democratic Society (the major student organization of the New Left), NUC had chapters in over 40 campuses across the United States. Although a considerable number of young radicals in 1968 chose to abandon the university to carry on the struggle outside academia, many wanted to balance both a radical approach to the institutions in which they were located (by radical teaching, curriculum reform, democratic struggles for control) with activism outside their work — community struggles against imperialism, racism, sexual inequality, and capitalist economic organization. NUC was a magnet for hundreds, then thousands, of like-minded radicals in the academy. Kampf was a leader nationally and in the chapter at MIT.

Legendary classrooms

In 1967, Kampf organized and became director of an organization of Cambridge academics called Resist, the first academic group devoted to supporting draft resistance to the Vietnam War. In 1968, Kampf was one of 130 MIT faculty members who signed an open letter to MIT’s president, Howard Johnson, urging him to end MIT’s relationship with the U.S. Department of Defense. Noam Chomsky was another, and for four years, the two of them co-taught an influential course called “Intellectuals and Social Change” that had hundreds of students — perhaps the largest enrollment in any humanities class in the Institute at any time before or since. Participation in the course set a significant number of students on the road to activism and to raising questions of social values.

As a teacher, Kampf was consistently both a generous force of inclusion and a prod of conscience. He taught subjects in American literature and culture, contemporary literature, and world literature — although the boundaries between those categories tended to melt away, as did strict delineations of field, of literary movements, of genre and form. The topics of Kampf’s subjects, like the famous sequence he taught called “American Voices,” ranged boldly and widely afield, organized around categories like “ballads from Goethe to Willie Nelson” and “songs by working-class women.” His knowledge was wide — he could quote pretty much any source in its original language — and his capacity to keep learning all-inclusive.

“A wild ride” through literary eras

In 1984. Kampf was the first male professor in the fledgling Women’s Studies program at MIT, and his support for the program was significant. He taught subjects in “Women’s Literature,” in “Men’s Sports,” and in “Practical Feminism” — in which students went into the community and worked in organizations such as Rosie’s Place (a women’s shelter) and the “Our Bodies Ourselves” storefront health information clinic.

He co-taught “Sex Roles in European and Latin American Fiction” with Margery Resnick, “a wild ride through literary eras, geographies, and styles because of his vast knowledge and conviction that there were almost no authors whose works were not amenable to productive interpretation of gender roles.” He was also well-versed about literature and the social construction of gender in areas of the world with which few at that time were familiar, introducing his colleagues to numerous African and Asian literary texts and essays.

The parallel career

His continual political involvement at all levels of networking and organizing was in many ways a parallel career to his academic work. Kampf played a key role in the development of “movement” organizations that opposed racism, sexism, homophobia, and war, and that supported Palestinian rights. Following its founding in 1967 in New York City, he set up the national office for Resist — an organization designed to support draft resisters in Cambridge. Across from the Post Office (where the FBI installed itself), the Resist office became a hub for academics involved in anti-war activity.

Other organizations in which he worked included the Ad Hoc Lebanon Emergency Committee, the Bethlehem Sister City Project, and the Center for Critical Education, which publishes the magazine Radical Teacher, for which he wrote and edited. He worked on many issues from organizing academics to oppose the war in Vietnam to Israel/Palestine; AIDS activism; the exploitation of adjunct faculty; the responsibility of intellectuals; and what “radical teaching” actually meant. For most of his life he was engaged with these and other political issues — about which he worried and thought and sought to change.

More mensch than ideologue

But Louis Kampf was more of a mensch than an ideologue. He loved to dance and took the floor whenever possible; one friend described him dancing after a meeting: “Acerbic and lyrical, all at the same instant and all showing on his face.” He knew volumes about the jazz of the last 60 years; many musicians knew him personally and cherished his knowledge and appreciation. He was passionate about all kinds of music, from grand opera, to early music, to jazz and country and everything in between. He could talk to anyone, and engaged everyone he met, opening himself to them and often hearing in response stories from their own lives. He spoke fluently about all aspects of his life and the world around him with great ironic humor.

Above all, Kampf was a great friend. He leaves behind an enormous number of people who deeply miss and mourn him and will carry his memory into the future.

For 30 years, Louis was the life partner of Jean Jackson, professor emerita of anthropology at MIT. He is also survived by his former wife, Ellen Cantarow of New York City, and a cousin, Howard Radzyner.

Sign Up For Our

Newsletter

Each day, we honor and remember those who have recently passed away.

Most Viewed

More

- Article Obituaries

- Celebrities

- Celebrity News

- Local

- News

- News & Advice

- NFL

- NHL

- Northside

- Norwin

- Obituaries

- Obituary

- Penn Hills

- Pirates

- Pitt

- Pittsburgh

- Plum

- Politics Election

- Sports

- Steelers

- Theater Arts

- Top Stories

- Travel

- Tribune Review Obituaries

- US-World

- Valley News Dispatch

- West End

- Westmoreland

- World